You can hear it in church. You can hear it at the corner store. You can hear it at the day care center, at the food pantry, and outside the elementary school. Most days in Lincoln Heights, a small majority-Black suburb 10 miles north of downtown Cincinnati, the gunfire starts in the morning and lasts through midafternoon, though sometimes it continues past sundown. On the playground at one public housing complex, the shots can drown out a conversation. They’re close enough to have a distinct sonic texture: a crackle, an explosion, an echo, usually in rapid-fire bursts. In some backyards, the blasts are loud enough to make you jump.

Multiple generations of Lincoln Heights families have lived their lives to the soundtrack of this gunfire. “It’s like birds chirping, or like traffic in New York City,” said Daronce Daniels, 34, a Lincoln Heights councilman and fifth-generation resident.

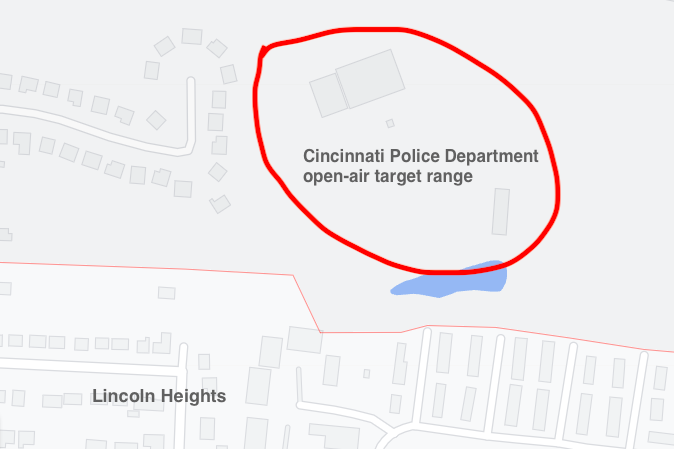

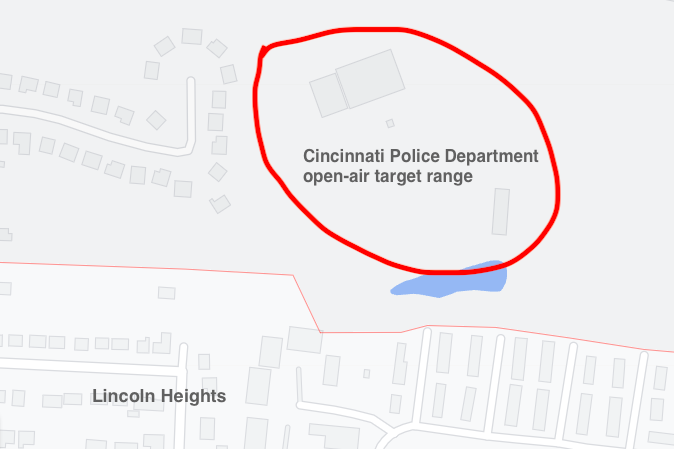

The shots are fired by the cops, as practice. For more than 70 years, the Cincinnati Police Department has owned the open-air target range that abuts the northern border of Lincoln Heights. Though CPD doesn’t police the towns that surround the gun range, every CPD officer trains there, as do some federal agents. In 2019, CPD used the range about 300 days of the year.

It’s the gunfire’s impact on children that most worries Alicia Franklin, 34, who lives with her mother and three sons in a tidy brick ranch-style home a quarter-mile from the range. I had just entered her living room when I heard her 11-year-old yell his own opinion on the gunfire from his room: “It’s annoying waking up to it!” Franklin wonders what the daily barrage is doing to her sons’ attention spans and stress levels. When her oldest son was attending school virtually last year, she worried that the sound interrupted his work. Franklin’s own colleagues have told her they can hear it during calls. The noise isn’t just distracting for her son—it’s embarrassing for her.

And the family’s proximity to the range has added a grim new layer to the discussions about police violence that Franklin would have had with her sons no matter where they lived. “That conversation is always just the difficult one. Explaining, you know, the reason why they have this gun range—they’re training,” she said. Franklin knows that Black boys and men are at particular risk for police violence, which makes it impossible to avoid what she sees as the obvious conclusion: “Basically, training to kill us. We get to hear them training to kill us.”

It’s not unheard of for police departments to train and test officers at locations outside their jurisdictions. Nor is it unusual for law enforcement agencies to use outdoor gun ranges; the Hamilton County officers who patrol Lincoln Heights train at one in a more rural part of the county. But an open-air police-run target range so close to a dense residential area is a rarity, presumably because municipal lawmakers don’t want to irritate their constituents. Therein lies the crux of Lincoln Heights’ problem: Though the gunfire principally affects Lincoln Heights and a cluster of homes in neighboring Woodlawn, the range is owned by the city of Cincinnati and sits in a third jurisdiction, the much more affluent village of Evendale, whose residential areas are largely protected from the noise by the buffer of a six-lane interstate and an expansive industrial zone. In other words, none of the public officials with the power to move the range are accountable to the people whose lives are most affected by it. To Lincoln Heights residents, it feels like an out-of-town company coming in to dump toxic waste in their backyards—an insult no whiter or wealthier community would be asked to accept.

The gun range was never supposed to be so close to people’s homes. In 1941, soon after the nearby Wright Aeronautical factory opened, a group of veterans employed by the plant built the range for their ex-servicemen’s club. Back then, the only other occupied building nearby was a school for the deaf. But after World War II, when the plant closed for a spell, the vets sold the range to the city of Cincinnati. The deal went through in 1946, the same year that Lincoln Heights incorporated. Over the years, every time Lincoln Heights leaders petitioned Cincinnati public officials to relocate it, their response was that the gun range was there first.

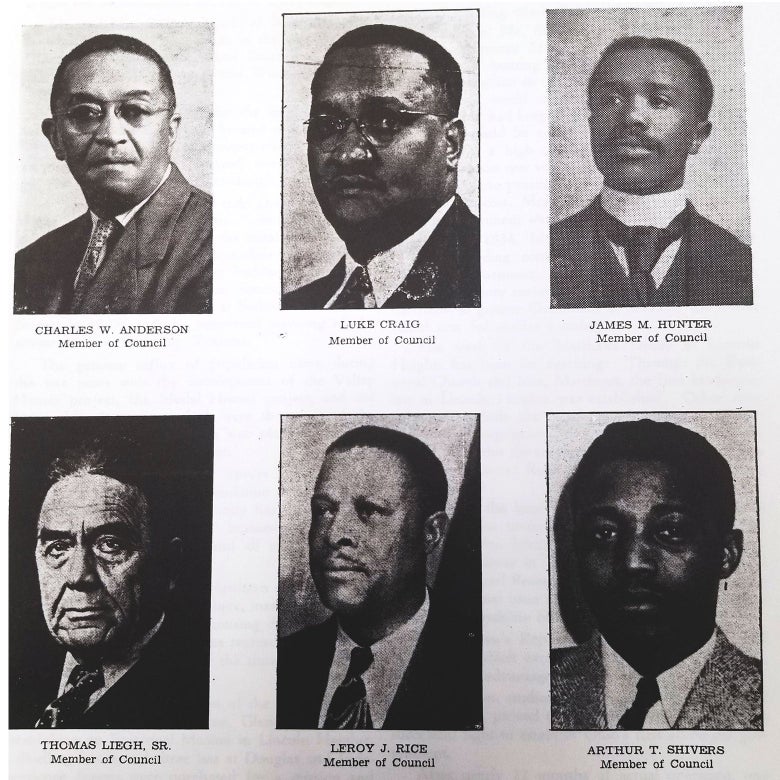

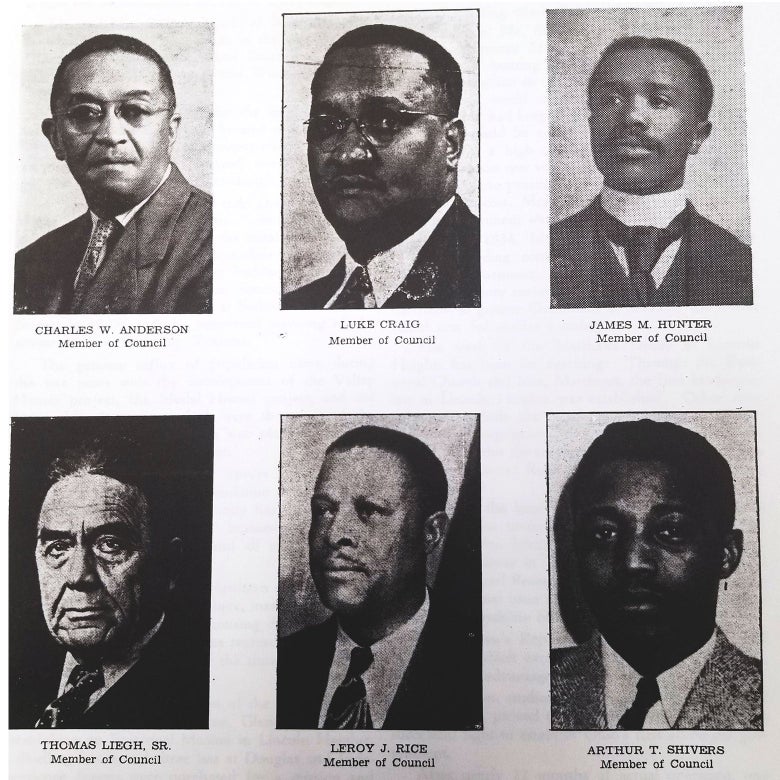

Which isn’t entirely true. The housing complexes closest to the range were built after CPD took ownership. But Lincoln Heights itself, the first Black self-governing community north of the Mason-Dixon Line, was born of grit and imagination in the 1920s. Black people were prohibited from buying land in much of Cincinnati proper at the time, so one group decided to build a town of their own in the unincorporated land north of the city—an area that seemed like an auspicious location for future development. Many of Lincoln Heights’ founders had moved to Cincinnati from the Atlanta area during the Great Migration, bringing with them agricultural knowledge that they poured into the town’s small farms and gardens. The lack of incorporation meant that there were no paved roads, no public amenities, and minimal access to running water or sewage systems. They built rain cisterns and whatever else they could to make their lives more tolerable.

“This is a community that really came from the dirt,” said Bill Franklin, 54. Franklin (who is not related to Alicia Franklin) grew up in a house built by his grandfather, who moved to the village from downtown Cincinnati because, Franklin said, “this was the happening Black suburb.” The goal was to build a town unfettered by the racist strictures that left Black people lacking upward mobility, public safety, and positions of power in white-run jurisdictions. When Lincoln Heights residents first attempted to incorporate in 1939, it was because they wanted those power structures for themselves. “Men were sick of working two jobs and then coming home to the chaos of open sewers and burning buildings and dark streets,” Alana Semuels wrote in “The Destruction of a Black Suburb,” a 2015 Atlantic article about the history of Lincoln Heights. “Someone needed to put in paved roads and electricity and inspect buildings to make sure they were up to code, and the county government nearby had no interest in doing any of that.”

If the town incorporated, the founders knew, it would also stand to reap tax revenue from the Wright Aeronautical complex, which had opened in 1941, just in time to build piston engines during World War II. There was plenty of space in the planned village boundaries—which comprised several unincorporated majority-Black subdivisions—for other industrial development, too. But the white communities that surrounded Lincoln Heights did not take kindly to such plans. Lockland, worried about economic competition, filed a formal objection with the county to the village’s incorporation. The manager at the Wright Aeronautical plant, who didn’t want his factory to be located in a Black municipality, fought back too, saying that his company owned the whole subdivision it sat on.

“That battle foreshadowed the age of colorblind racism, where you would use other forms of arguments other than race,” said Henry Louis Taylor, Jr., director of the Center for Urban Studies at the University of Buffalo, who wrote his dissertation on the history of Lincoln Heights. “The argument was that Lincoln Heights represented a spread of the slums into the suburban areas.”

As Lincoln Heights’ incorporation proposal languished, the county doled out valuable land—from within the borders Lincoln Heights had proposed for itself—to white towns. The Wright plot, after successfully avoiding inclusion in Lincoln Heights, ended up going to Evendale and helped that town prosper. By the time the county let Lincoln Heights incorporate, its boundaries contained only about one square mile: just 10 percent of the land in the founders’ initial plans, with no factories or other industry to generate tax revenue, and no more space to grow. “It wasn’t a dream deferred, like Lorraine Hansberry talks about. It was a dream crushed,” Taylor said. “Because it’s not like a lot of other places where you didn’t have a shot. [The founders] had a shot to have a very different reality, because they got in right at the right time. White folks knew they were there at the right time, and they just used racism to defeat that.”

Still, there was a period right after incorporation when things seemed to be going well. Black residents entered public office and got jobs with their own fire department and police force. Small businesses—stores, bars, a skating rink—flourished, and residents could also find well-paying jobs at the former Wright plant, which was started up again by General Electric a few years after the end of the war. Some current residents of Lincoln Heights still live in a home or on a piece of land inherited from their ancestors, a relatively rare privilege for Black Americans.

But every decade brought a new scourge. Industrial jobs started disappearing in the 1970s. Then there was crack, the 1994 crime bill, and the Great Recession. Between 1960 and 2019, the village population dropped by more than half, from 7,798 to 3,354. Home values have plummeted, too, even as they’ve risen in neighboring communities. Seventy percent of Lincoln Heights children live below the poverty line. The village—with fewer than 5,000 residents now, that’s how it’s officially classified by Ohio—no longer has a community center or a library. In 2014, Lincoln Heights was forced to disband its own police department after it was dropped by its insurance provider for attracting too many lawsuits. Now, the county sheriff’s office polices Lincoln Heights, a shift that some residents say has worsened community-police relations and taken away local jobs.

All the while, the gunfire from the CPD range has continued. “There are a lot of people who took over their family’s land,” said Carlton Collins, 32, who grew up in Lincoln Heights and used to run an outreach center there. “So they might own the house. They’ll rent it out, but they wouldn’t necessarily move back or invest the dollars to then make that their home, because they don’t want to move back to where there’s gunshots.”

The closest Cincinnati has ever come to moving the range was a 1999 proposal by then–Cincinnati Mayor Roxanne Qualls, who suggested that the city close the range and give those dozen-or-so acres to Lincoln Heights as a potential commercial zone that could boost the village’s dwindling tax base. According to a 1999 report from the Cincinnati Enquirer, Evendale’s mayor was on board with the annexation “as a goodwill gesture to financially struggling Lincoln Heights as well as a trade of land that would straighten out Evendale’s boundary.”

But Cincinnati police fought the proposal. The firearms training commander at the time dismissed suggestions that residents were bothered by the noise and told the Enquirer that moving the range would waste a $1 million investment the city had made in range improvements. The then-president of the Cincinnati police union went one step further. “If council passes this motion, they may as well be spitting on the graves of Dan Pope and Ron Jeter,” he said, referring to two officers who were killed in the line of duty 15 months earlier. “And that would show council’s true colors as it relates to the safety of their police officers.” The proposal failed.

Councilman Daniels has spent most of his life in and around Lincoln Heights. As a child, he and his friends would cross the creek next to a basketball court to get to the lush wooded area that surrounds the range. From there, they’d sneak onto the range and look for bullet casings, just for the thrill of trespassing without getting caught. Various fencing reinforcements have been erected in an attempt to keep people out of harm’s way since then, but kids are still kids: curious, unafraid, always climbing, small enough to fit through holes, and persistent enough to create them. Several parents told me about children who made a game of trying to sneak onto the range.

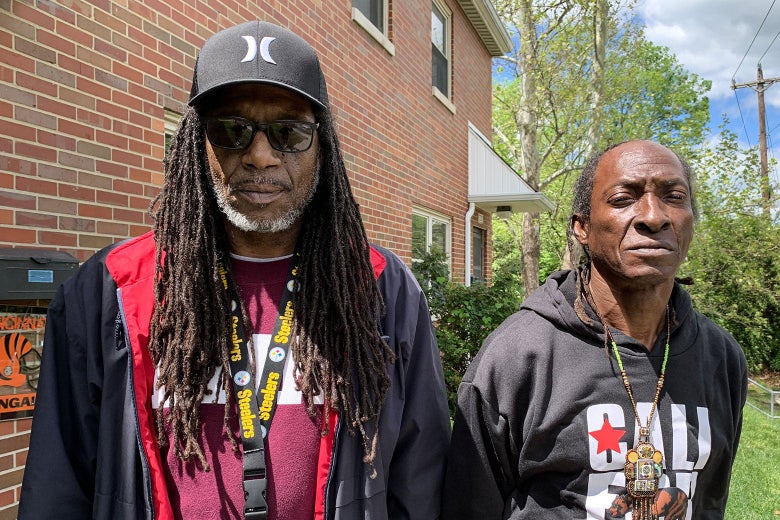

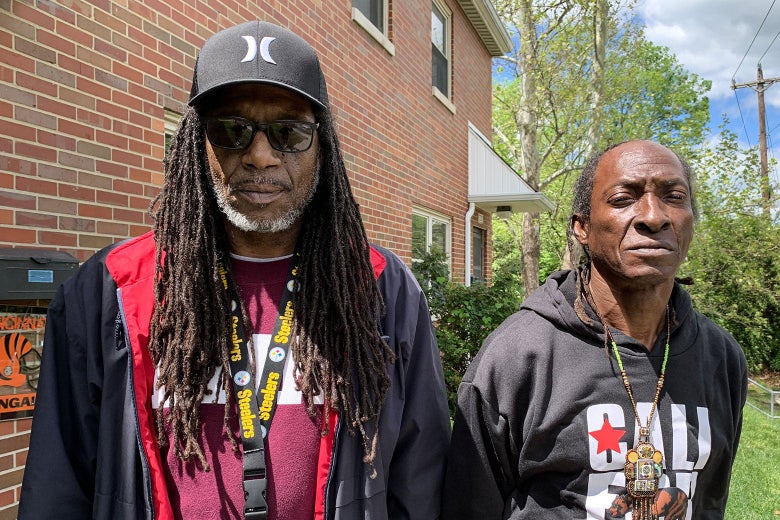

Daniels, who attended Elon University on a football scholarship, remembers bringing his roommate home during spring break and seeing him flinch at the gunshots Daniels no longer noticed. Ever since then, Daniels has made a habit of watching how new people adjust to the sound. On a sunny Wednesday afternoon in May, I met up with Daniels and Collins at Marianna Terrace, a 76-unit public housing complex that sits at the northeast corner of Lincoln Heights, hemmed in by I-75 and the CPD gun range. A chain-link fence spanned the terminuses of the complex’s four dead-end streets, behind which lay a dense patch of woods. At the end of one street, a honeysuckle bush threatened to engulf a faded sign on the fence. “NO TRESPASSING – TARGET RANGE – CINCINNATI POLICE DEPT,” it read.

I’ve heard gunfire before, and I expected to hear it here. But the proximity and volume were still a shock. One second, I was admiring the landscaped yards of the complex. The next, I was frozen in place, filled with adrenaline. “Christina, the look on your face just now? I wish I took a picture of it,” Daniels said, laughing drily.

Dale Holland, 61, has lived in Lincoln Heights his whole life, but never closer to the gunfire than his current home in Marianna Terrace. “I thought it would be a nice spot for me. I take care of the young, make sure no one gets hurt. I teach everybody a little something around here,” he said. A master gardener, Holland has turned the mulched flowerbed in front of his townhome into a plot for cabbage, potatoes, and peppers. A potted strawberry plant on the steps up to his front door was just beginning to bear green fruit when I visited.

But the incessant gunfire has taken its toll. The stress has interfered with Holland’s appetite, sleep, and mood. He recalls the first few times his grandson, who lives elsewhere in the village, came to visit, before he was old enough to be accustomed to the sound. The young child shook and grabbed at his grandfather, confused and upset by the noise. “It really infuriated me,” Holland said.

Steven Easley, 43, grew up in Cincinnati and attends Missionary Baptist Church in Lincoln Heights. In the mid-2000s, he served in Iraq as a member of the Army Corps of Engineers. When he returned to Lincoln Heights, “the first thing you hear is—you sound as if you’re under attack,” he said.

One Sunday, as he and his wife were driving back from church, Easley heard the gunfire and instinctively pulled over to the side of the road. “I immediately went to a space of an evasive maneuver. You pull over, you get out the car and get a line of sight of what’s going on,” he said. “And my wife, she was like, ‘What in the world?’ And I realized, I looked around like—I’m home. … I’m actually safe. There’s no lives on the line right now.”

But an open-air gun range in a densely populated area will never be completely safe. In 2008, a stray bullet ricocheted off a metal target and flew over a retaining wall, breaking the windshield of a civilian’s parked car. Luckily, the car was unoccupied. CPD requested $400,000 for safety modifications to the range, including a roof that would partially cover it. But Cincinnati councilmembers “weren’t so sure one stray bullet was enough to prioritize the range improvements over other department needs,” the Enquirer reported.

There’s another cost to living so close to constant gunfire: Most residents no longer start at the sound of what almost anywhere else would signal the threat of violence. Bill Franklin has coined the term “Gunshot Immunity Syndrome” to describe the way Lincoln Heights kids lack the critical reflex to run or hit the ground when they hear gunshots. As in so many communities in America, gunfire here happens off the range, too. Holland is haunted by the memory of the death of his nephew, who was shot and killed a couple of streets up from Holland’s home one afternoon. If Holland heard the gunshots, he didn’t think anything of them. He learned of his nephew’s shooting by phone; by the time he arrived at the scene, his body was being taken away.

“Nobody was looking out for him,” Holland said. “He’s sitting in the car dying? Come on, now.”

It was only when Daniels won a seat on the village council in 2017, making him the youngest member by nearly two decades, that he began to wonder if he might be able to do something about the range. Over the course of campaigning, he and a few fellow candidates built a network of contacts to better assess the community’s needs. They started a nonprofit called the Heights Movement to continue that work outside of Daniels’ council responsibilities.

Relocating the range is one of the Heights Movement’s main objectives. Daniels and the others believe that none of the other ambitions they have for the town will be possible while the sounds of police gunfire are as unremarkable as birdsong. Businesses don’t want to open in a place that sounds like it’s under constant attack. People with the money to live in more peaceful locales won’t build a life there either.

So why has Daniels stayed? He has watched other parts of metropolitan Cincinnati, including the West End and Over-the-Rhine, gentrify in ways that displaced longtime Black residents. It’s made him all the more grateful for the all-Black village leadership and Black land ownership of Lincoln Heights, which makes it much less likely that residents will get pushed out of their own neighborhood. “Where else do you have a place where African Americans truly own everything?” Daniels said. “Like, you might have a Black neighborhood, but at the end of the day, it belongs to the city. Our Black neighborhood belongs to us, so we’ve got to make sure to do the right thing by it.”

Daniels has a deep affection for Lincoln Heights—his license plate reads “ZN15,” shorthand for Zone 15, a popular nod to the village’s ZIP code. Driving around town with one of his oldest friends, Douglas Cooper, 34, the men point out empty buildings and overgrown lots where neighborhood institutions used to stand, like they’re narrating scars on an autopsy report. There was the skating rink and movie theater, a motel, a nightclub, a barbershop that was owned by Cooper’s great-grandmother, a place where James Brown supposedly used to hang out in his King Records days. It’s now a parking lot. A quiet street with several well-kept houses and one hollowed-out grocery store used to be “the hot spot,” Cooper said, a main drag that boasted several such businesses.

At the center of town is a scar so painful it’s more like a gaping wound: a pair of abandoned buildings that once housed a recreation center and an elementary school—once “the heart of the community,” Daniels said. “And now, it’s kind of like the thing that’s draining the life out of the community.” When the rotting recreation center, once run by the YMCA, closed in 2003, Daniels and his peers were teenagers suddenly left without a place to release their after-school energies. Teens from varied backgrounds and socioeconomic situations used to mingle, swim in the pool, and attend a program for young fathers. Daniels and Cooper provide an example of a deep friendship between local kids with different upbringings—Cooper grew up in Lincoln Heights, but Daniels lived right across the border in neighboring Woodlawn, in a cul-de-sac of single-family houses with two-car garages and manicured lawns. (Despite their polished appearance, those homes are subject to some of the area’s loudest gunfire, as they’re less than 100 yards from the main CPD target range building.)

“I’d always mess with Daronce, ‘Oh man, you a suck up!’ He had a whole lot more focus,” Cooper said. “He had a mom and a dad. I’d been like, ‘Boy, you got a real all-American family! Y’all living the American dream.’ So he had that structure and that discipline to keep him grounded.”

Kids who didn’t have stability at home, but who gained a semblance of it at the Y, were out of luck when it closed. “That’s when you had different little gangs sprouting up, because now there’s nothing to do,” Cooper said. Today, Daniels can’t drive by the old YMCA without remembering the boys their generation lost to drugs, guns, and prison.

He and Collins, who also leads the Heights Movement, turned their attention in earnest to the CPD gun range in 2019. That year, a few months after he’d visited an open Cincinnati City Council meeting to voice concerns about the range, Daniels spotted Cincinnati Council Member P.G. Sittenfeld and Cincinnati Mayor John Cranley at a church opening. “And I said, ‘Excuse me, about this gun range?’ And they both looked at me like I had a daggone horn growing out of my head,” Daniels said. “ ‘What gun range? What are you talking about?’ Like they didn’t even know it existed.” None of the officials Daniels and Collins approached seemed aware that CPD officers trained on firearms at a facility in a totally different jurisdiction. Lincoln Heights Mayor Ruby Kinsey-Mumphrey said she has invited Cranley to visit her and hear the gunfire in Lincoln Heights on several occasions, but he hasn’t taken her up on the offer.

While Daniels and Collins strategized from an activist perspective, Kinsey-Mumphrey, 56, took a more procedural tack, aware of the racial stereotypes that have historically led other public officials in the area to write off Lincoln Heights’ leadership. “Since I’ve been in office, I have worked very hard to try to change the narrative of how people view the Village of Lincoln Heights,” she said. “I do know you can’t go in being overaggressive in trying to get people to work with you. That has hurt the village for decades. And you need individuals to help you. We cannot do it by ourselves.” In early 2019, she began talking to the mayors of the other surrounding towns about making a unified request that the target range be moved. In July 2019, the mayors of Lincoln Heights and Lockland and the soon-to-be mayor of Woodlawn sent a letter to Cranley, requesting a meeting with him and the Cincinnati City Council. “Our immediate need and the collective task is simple,” it read. “Eliminate or drastically reduce Firing Range noise!”

It took a few months for the mayors to see results. First, the Cincinnati city manager produced a memo on what a new facility would require. It listed the active shooting hours as 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. on weekdays, in addition to two evenings and four Saturdays per year. When Kinsey-Mumphrey read the memo, she laughed. She’d often work late hours at the village municipal building and hear gunfire from the range as she was leaving, long after the workday was done. “Since I’ve been the mayor, nothing has ever come across me, no letter, saying, ‘Hey, this is the schedule, we’re gonna be shooting at this particular time,’ ” she said. “So when I saw [the memo], I was salty, as the young folks say. I knew that wasn’t true. I’m like, ‘Oh, OK, y’all got a schedule? How come I hear it past 3 o’clock?’ ”

In December 2019, Kinsey-Mumphrey and the mayor-elect of Woodlawn appeared before a Cincinnati City Council committee to make their case. In response, the committee commissioned a study of options for reducing noise pollution from the range. The report, published in February 2020, offered options that ranged from sound-blocking trees to a $2.7 million full enclosure of the existing range. A few months later, the three towns had rejected the noise reduction options. They intended to hold out for full relocation—but the committee chair, Vice Mayor Christopher Smitherman, told the Enquirer that if they wanted that, it would be up to them, not Cincinnati, to pay for it. “The shooting range has been there since the 1940s,” he said. “Any development that has happened has happened with the understanding the shooting range is there.”

A turning point in the activists’ efforts occurred in late 2019. Collins wrote a brief about the range, framing the issue as a health risk to local children, and started carrying copies around whenever he thought he might run into someone with the power to change things. He and Daniels brought the document to a constituent luncheon held by Ohio Sen. Sherrod Brown. In front of the crowd, Daniels raised his hand and asked Brown what he could do to help relocate the CPD range. What happened next, Daniels said, was like “the Avengers coming together.” One of Brown’s staffers, who lives in a town bordering Lincoln Heights, took an interest in their case. Renee Mahaffey Harris, president of the Center for Closing the Health Gap, a local community health organization, was also at the event and introduced Daniels and Collins to Cincinnati Council Member Jan-Michele Lemon Kearney. Soon Brown’s office was raising the possibility of $13 million in federal Housing and Urban Development funding for relocation, since the range hosts trainings for federal officers, and Kearney was calling for a public hearing with resident testimonies. Suddenly, it wasn’t just people from Lincoln Heights who were making noise about the range.

To help the activists determine whether the shooting was affecting residents’ hearing, Brown’s office connected them with Brian Earl, an audiologist at the University of Cincinnati. In September 2020, Earl and Collins pulled up to the Marianna Terrace playground, windows down. “Before I got out of the car, I could hear the booming. It was just like, eye-widening booming,” Earl said. He could feel the acoustic reflex, a twitchlike contraction of small muscles in the middle ear meant to protect us from loud stimuli. For Earl, that was an immediate red flag.

“The gunshots are quick, but they’re intense. Our ears can handle a little bit of that intense but quick, but it’s annoying, and it can be damaging over time,” he said. In a 15-minute recording he made, he found that the noise regularly spiked over 100 decibels. That’s a volume that, if sustained, would normally warrant ear protection.

Averaged out over the course of an hour or day, those quick bursts might not add up to an unsafe noise “dose,” and noise-induced hearing loss often accumulates slowly over decades due to a variety of stimuli. But hearing loss is just one of Earl’s concerns. As he stood listening to the booming, Earl saw a young girl walk by undisturbed. Her lack of reaction indicates “a developmental change,” Earl said. It made him think of research that “suggests that background noise can impact the cognitive awareness of children and affect their learning.” Earl intends to make an eight-hour recording next month to get a better sense of the dose endured by people who live near the range, and residents have installed apps on their phones that will let them record snippets and send them to Earl.

On Juneteenth 2020, the Heights Movement held a rally at the range and a protest caravan around the village. A demonstration this small—about 150 people attended—might have seemed inconsequential in other locales. But it changed the mind of state Rep. Sedrick Denson, 33, whose family name still stands on a now-closed Lincoln Heights grocery store. At first, when Daniels approached Denson about his intention to get the range closed down, “even I was guilty of probably saying to him, ‘Well, that’s a huge order, and I don’t know how far you’re going to get with it because it’s been around,’ ” Denson said. “And he goes, ‘Oh, no, it’s got to go.’ ” The rally nudged Denson to consider that this movement might be a new start for Lincoln Heights—grassroots political organizing and protests aren’t as common as the village’s radical roots might suggest.

Then, in October, the Cincinnati City Council held a hearing on the effects of the range. It was the first time in the seven decades since CPD began shooting there that Lincoln Heights residents had been able to speak on the record, in an official capacity, about what it was like to build a life against a backdrop of incessant gunfire. Alicia Franklin shared a video of her then-4-year-old son covering his ears on their stoop as he complained about the audible shots. “He used to get startled and scared when he heard those gunshots, and that video wasn’t long ago,” Franklin said in her testimony. “Now, they don’t phase him, which is very concerning. It’s like he’s conditioned to think it’s OK to hear the gunfire.”

An image of a child protecting himself has a way of making a political issue feel deeply, urgently personal. Now, the Cincinnati City Council seems to be seriously considering the prospect of moving the range entirely instead of merely building a noise-reducing wall or partial enclosure. CPD estimates that building a new outdoor range would cost around $4.6 million, plus the price of a few dozen acres of land. (According to Kearney, Cincinnati has rejected the prospect of an indoor range, citing concerns for the health of CPD officers.)

“City of Cincinnati council members, the administration, and police sat down with Lincoln Heights administrators for a public discussion about the relocation of the gun range,” Cranley said, in a statement from a spokesperson, in response to a request for comment for this story. “The City has offered to move this training facility once an alternative location is found and secured.” (His statement also noted that “the Cincinnati Police training range has been at its current location for more than 70 years—before an established residential community surrounded it.”)

Cincinnati Police Chief Eliot Isaac said in his own statement that the CPD “is not opposed to moving the gun range from its current location in Lincoln Heights.” “Right now, there is no proposed solution to the issue,” Isaac wrote. “It is our desire to be good neighbors and to cause no harm to the communities that we serve.” A CPD spokesperson did not make Isaac available for an interview and, in response to a list of detailed questions about the range’s history and future, declined to comment.

Council members and CPD brass have looked at several potential sites for a new range in the area. The residents and leadership of Colerain, a comparatively conservative and sparsely populated township a few miles west of Lincoln Heights, have indicated that they may be open to a new facility on the land next to an existing outdoor range in a remote location, where the county sheriff’s department currently trains. In May, Hamilton County commissioners offered to use $5 million in county stimulus funds to support the range’s relocation. Between that money, the federal funds both of Ohio’s senators believe may be available, and capital dollars from the state that Denson has promised to push for, Cincinnati will no longer have expense as an excuse to delay moving the range.

For decades, Lincoln Heights leaders who wanted to organize against the range had been battling a normalizing effect that afflicts communities with structural disadvantages. But the new information and conversation have changed things, said Harris, who runs the community health organization. Research about food deserts has found that “nobody thinks they live in a food desert until you tell them it’s a food desert,” Harris said. “It’s just what they’re used to.”

As Daniels sees it, the stakes of the fight to move the gun range go far beyond the noise nuisance. If it succeeds, he hopes, residents will recognize their power, take greater pride in their hometown, and be motivated to pitch in on other efforts to reverse the village’s downward trajectory. If it fails, it’ll be read as evidence of their powerlessness, one more reason to suppress their hopes for a better future, and yet another reminder that their well-being doesn’t rank on any public official’s priority list.

Daniels also sees the relocation of the range as an opening for a more thorough reckoning with the ways surrounding towns have profited at Lincoln Heights’ expense. But this may be his toughest battle of all. Evendale leaders are no longer willing, as their predecessors were in 1999, to cede the range property to Lincoln Heights. In fact, the town’s plans for AeroHub, a forthcoming advanced manufacturing and technology corridor across the highway from the GE complex, include the CPD range as a possible site of future development. Evendale is “really allowing us to fight this fight for them, and I think they’re just gonna take the spoils of war,” Daniels said on a Zoom call with me and Collins in April. “Bro, you just let them off super easy,” Collins said. “Evendale has never had an issue with the gun range being there … [but] they were down to get it moved when it became economically advantageous for them to get it moved.”

Evendale Mayor Richard Finan disputes that characterization. According to Finan, when Kinsey-Mumphrey came to him in 2019 to ask what could be done about the noise from the CPD range, he’s the one who suggested they send that letter to Cincinnati leadership. “That was the beginning of where we are today,” he said. (Kinsey-Mumphrey says they were both responsible for the idea.)

The Heights Movement has issued a list of demands its members say Lincoln Heights is owed from Cincinnati due to the lingering harms of the gunfire. It includes grants for public health and funding for mental and behavioral health programs in schools. In keeping with their focus on youth, movement leaders are asking that these reparations extend for 18 years past the date of the last bullet fired at the CPD range.

But not even Kearney, the activists’ primary ally on the Cincinnati City Council, will entertain the possibility of Cincinnati compensating Lincoln Heights residents for 70-plus years of backyard gunfire. “I think Cincinnati would argue we’ve been there a long time,” she said. “So, Lincoln Heights and the gun range grew up together, and also Cincinnati doesn’t have any money. However, Evendale, I think people need to take a look—I’ll point the finger over there.” Kearney thinks Evendale should offer Lincoln Heights some type of redress for its possession of the land on which the Wright Aeronautical plant–turned–GE complex sits. Once Evendale develops the CPD range property, Kearney said, “they need to make sure they give some of that tax money to Lincoln Heights.”

Finan said he does not intend to consider any revenue-sharing agreement with Lincoln Heights if and when the range site is sold and developed. I asked if he could see where Kearney was coming from when she said that Evendale owed Lincoln Heights restitution for the racially discriminatory way their town boundaries were drawn, since it consigned the municipalities to very different futures from the start. “No, I don’t agree with that at all,” Finan said. “None of the good burghers in Lincoln Heights say that. That’s just not the facts.”

The upshot is that, as it stands, moving the range would be a huge accomplishment for Lincoln Heights activists—but one that could also cement a cross-generational pattern of Lincoln Heights as the losing party in lucrative municipal real-estate deals. Evendale’s willingness to back Lincoln Heights’ efforts may stem in part from its desire to develop the range site. If it does, and if Lincoln Heights gets no part of the profits, the echoes of the Wright factory episode would be impossible to ignore.

The question of what Lincoln Heights deserves is deeply personal for Daniels. “My grandfather always grew me up on stories about what you’re supposed to do, what he didn’t like, and things that he’d always been trying to fight,” Daniels said. One of those things was the CPD gun range. Now, Daniels and his wife are raising his family’s sixth generation in Lincoln Heights—their 12-year-old daughter and 3-year-old son. In moments of optimism, Daniels imagines a future Lincoln Heights transformed by his work and the work of his neighbors, a place where any parent would want to raise a family. But other times, hearing the gunfire outside his home and his son’s day care makes him question himself as a parent. If he doesn’t succeed, he said, it won’t just feel like he let down his community and his grandfather—it will feel like he let down his child, too.

At 94, Daniels’ grandfather, Elbert, still talks about his own stint on the village council in the 1970s, one of several leadership positions he’s held since he was born in a Lincoln Heights house just a half-mile from the home where I met him. Like many of the houses in his part of town, Elbert’s two-story home was built in the 1920s, back when members of the village would all come together to construct homes for new residents. Sitting on his easy chair, surrounded by photos of his grandchildren, Elbert recalled the feeling of purpose he had when he was elected, followed by the frustration of realizing that many of the objectives he’d set for himself would remain out of reach. This included ridding his community of the CPD gunfire, a goal Lincoln Heights didn’t have the political leverage to achieve. He’s waited 50 years for his grandson to have another chance. “If he could get that gun range gone,” Elbert said, “that would be one of the biggest things that’s happened.”

On my last day in Lincoln Heights, I told Daniels that despite the raw deal the village had been dealt at every turn, it still seemed to have considerable potential—Black land ownership, intergenerational roots, the community pride of a small town with proximity to a major city. He shook his head. “It sucks. The worst thing in the world, my father used to tell me, is potential,” he said. “Because it’s something that’s not being used.”

He went on to recount the history of Black resilience and innovation—through enslavement, Reconstruction, the civil rights era—and the formation of Lincoln Heights. We were sitting next to the gun range fence, watching the kids of Marianna Terrace play while their parents chatted nearby. “I’m betting on them,” Daniels said, pointing toward the cluster of people. “That if they now see that a better life is possible, by getting this thing moved, they could do anything. Because if you look at the history of not just our community, but our people, we’re overcomers. We’re overachievers. I’m just betting on history, I guess.”

"hear" - Google News

September 27, 2021 at 06:00AM

https://ift.tt/3ueCkeS

Lincoln Heights' fight to move the Cincinnati Police Department gun range out of earshot of their town. - Slate

"hear" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2KTiH6k

https://ift.tt/2Wh3f9n

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Lincoln Heights' fight to move the Cincinnati Police Department gun range out of earshot of their town. - Slate"

Post a Comment