On Monday, city officials in Elizabeth City, North Carolina announced that they would be declaring a state of emergency ahead of the potential release of body cam footage of last week’s police killing of Andrew Brown, Jr., an unarmed 42-year-old Black man. Law enforcement and elected officials in Elizabeth City are following a familiar playbook for police departments that face calls for reform following high-profile killings of unarmed civilians, who are often Black: close ranks, delay information, and then, when the release of damaging information is imminent, preemptively attempt to shut down community protests.

Following the police killing of Brown, Jr., the sheriff’s department waited three days to respond to community demands to release body camera footage from the incident. In a prerecorded video, Pasquotank County Sheriff Tommy Wooten claimed he had no power to release the footage. The Brown family and their attorneys finally saw 20 seconds of redacted footage on Monday, six days after Brown’s killing; that same day, Elizabeth City Mayor Bettie Parker declared a state of emergency “to ensure the safety of our citizens and their property.”

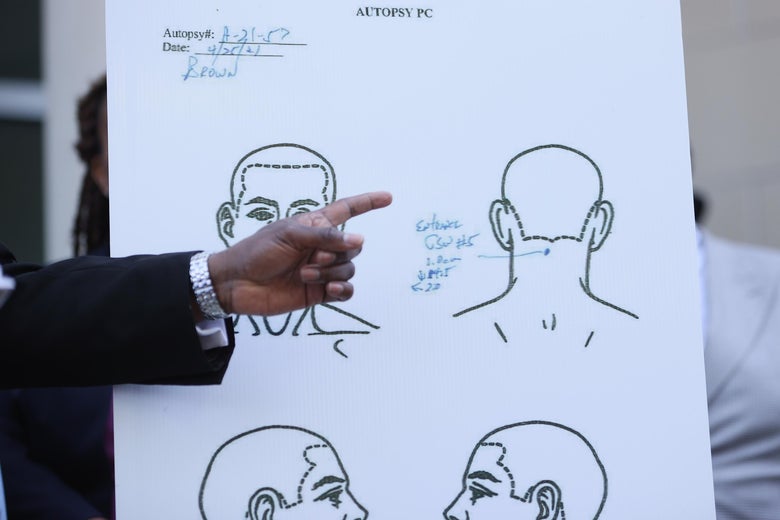

In Elizabeth City, hundreds of protesters marched, disrupting traffic and calling for the resignation of Sheriff Wooten, County Attorney Michael Cox, and others they say are denying the community full transparency. On Tuesday, autopsy information showed that Brown died from a bullet wound to the back of his head.

Elizabeth City has been girding for massive backlash to the shooting and community activists say that local officials have already used extreme measures to preemptively try to shut down dissent. Public schools moved to remote learning for the rest of the week, and students at Elizabeth City State University, a historically Black institution, were asked to leave their dorms.

Dawn Blagrove, executive director of EmancipateNC, has traveled from Durham to Elizabeth City to give support to protesters. She says local outrage is more than a political response, but the reaction of a tightknit community losing one of their own. Attempts to stifle these community voices is only likely to backfire.

“This is a small community,” Blagrove said. “Very few of [the protesters] do not know Andrew Brown or someone connected to his family personally, and their pain is compounded by the fact that their officials and county commissioners have taken such an antagonistic position toward transparency, toward the community.”

Blagrove also believes that Wooten’s claim that his sheriff’s office doesn’t have any ability to make the video public is a poor excuse for inaction. Police bodycam footage is not public record in North Carolina; releasing footage to the public requires a court order from a judge. But Blagrove, an attorney, says that under state law Wooten is custodian of the footage, could have shown it to the family at any point in the last week, and should have immediately filed a motion requesting its release to the public. Instead, she said, “they dragged their feet,” further traumatizing the family, and used the emergency declaration to shift attention away from state-sanctioned violence and onto the protesters.

So far, marchers have been peaceful, according to Blagrove, despite attempts by counter-protesters to engage violently. “The violence we see is always coming not from the folks [who] are most hurt, demanding that their humanity be seen, but by the people who think acknowledging someone else’s humanity diminishes their own,” said Blagrove.

Elsewhere in the state, this pattern is all too familiar.

Sylvester Allen, a lifelong resident of Alamance County who has been involved in numerous protests and marches there, including a Halloween voting rights march last year where dozens of people were pepper sprayed, sees a clear parallel between what has happened in Elizabeth City and the history of policing in his own county. “It’s sad, it’s repellent,” Allen told me. “The first thing that happens is you hear about the killing. The next thing you do, is you try to uncover what the police are hiding. It’s stomach-turning that that’s the process.”

Faith Cook, a community organizer in Alamance, said she went to the Graham town square to protest on Tuesday night because she couldn’t take a day off of work to drive to Elizabeth City, more than three hours away. “Elizabeth City was weighing on me,” she said. “I wanted to scream, I wanted to yell.”

As founder of Light of Alamance, Cook has worked to demand accountability and justice in her own county, where in January 2020 another unarmed Black man, Jaquyn Light, was killed by police after he allegedly fled police who were serving an arrest warrant. The officer who killed Light did not turn on his body camera until after the shooting. He was not charged or fired. Again, this is par for the course in parts of North Carolina. Just last month, the town of Graham hired Douglas Strader, a so-called “wandering officer” who had been fired by Greensboro Police for shooting his gun into a fleeing vehicle. Given how Alamance handles both protesters and police violence, Cook fears for her family, including her 12-year-old daughter, who last August was almost run over by a white woman yelling racial epithets.

What is happening in Elizabeth City—with public officials clamping down on dissent even before everything about Brown Jr.’s killing is known publicly—is very familiar to community activists in other parts of the state. Though protests in Alamance over past police violence have been peaceful, city and county officials have used frequently-changed ordinances to try to shut them down, and elected officials are closely aligned with law enforcement. “There have been no broken windows, there’s been no graffiti,” said Cook. “But they keep adding different ordinances—now if you have more than ten people gathered, you need a permit. I don’t understand why they’re trying to silence the people. Our voice is the only thing we have.”

On Tuesday, protesters in Graham plan to gather again to demand the release of the body camera footage that will show the world what happened to Andrew Brown, Jr. Meanwhile in Elizabeth City, those who take a long view see the 8:00 p.m. curfew and university and school transitions to remote learning as part of a dark history.

“North Carolina, South Carolina are where slave patrols started,” said Blagrove. “This curfew is an extension of control of black and brown bodies.”

Though the state’s Democratic Governor and Attorney General, Roy Cooper and Josh Stein, have both called for the video’s release, Blagrove says that is not enough. “They should be on the ground in Elizabeth City right now to ensure that the family is treated fairly and that law enforcement officers are held accountable,” she said.

As for the rest of us? We need to push back against law enforcement and public officials in our own communities who seek again and again to stifle opposition to police violence. And those of us who can will need to watch the video of Andrew Brown, Jr.’s final moments, when that footage is released.

“We have to face as a nation the horrors of being Black in America and living in a carceral state,” Blagrove said.

"news" - Google News

April 28, 2021 at 07:01AM

https://ift.tt/3xwERlW

In North Carolina, a Familiar Pattern After the Police Killing of Andrew Brown, Jr. - Slate

"news" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2DACPId

https://ift.tt/2Wh3f9n

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "In North Carolina, a Familiar Pattern After the Police Killing of Andrew Brown, Jr. - Slate"

Post a Comment